UPDATE Nov. 10, 2023: Mike Bisek turned 100 earlier this year, but still has not received the Purple Heart for which his friends have advocated.

By Cindy Hadish/Homegrown Iowan

It was 1944.

U.S. Army Air Corps photographer/gunner Mike Bisek and fellow crewmates bailed out over Nazi-occupied France after their B-24 bomber was hit by enemy fire during their final bombing mission on railroad yards in Munich, Germany.

For weeks, with aid from the French Maquis resistance, they survived with little food or proper gear in the Alps, helping the French Underground evacuate a hospital and evading German troops.

MORE: See what two sisters returned to Mike Bisek from WWII.

As U.S. forces made their way to liberate the region in August 1944, Bisek was shot in the leg — by friendly fire.

Now, 78 years later, efforts remain underway to see that the 99-year-old Cedar Rapids man receives the Purple Heart he was never awarded.

“Mike deserves the Purple Heart,” said Richard Pohorsky, whose father worked with Bisek at Iowa Manufacturing in Cedar Rapids and who is determined to see that his friend receives the medal. “You would have to look long and hard for a more decent, humble and honorable man.”

Already, the Air Force Board for Correction of Military Records denied Bisek’s request to change his discharge record, which omitted the gunshot wound.

While his military medical records note the bullet wound to his right thigh and hospitalization in Italy in 1944, his honorable discharge papers recorded “none” for wounds received in action.

Taylor Foy, communications director for Sen. Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa), where Pohorsky turned for help, said because Bisek’s injury was not a “direct or indirect result of enemy action,” he doesn’t qualify for the Purple Heart.

“We’d be happy to take another look at the case if there is a change in policy,” Foy said, citing the Army’s decision.

Pohorsky, though, called the criteria “ambiguous and confusing.”

He cited other Purple Heart recipients, including an Iowan wounded by a fragment from a German rifle grenade that was accidentally detonated by a French citizen.

“Mike’s wound is similar,” Pohorsky said.

Bisek said the quest began when he approached a veterans organization about his discharge record, which omitted his injury. That official said he likely qualified for medals, including the Purple Heart.

His family, however, received a rejection letter from the Air Force Board for Correction of Military Records, stating the board was divided in its recommendation, but the agency director concluded there was insufficient evidence that an error had occurred.

“They said you had to be injured by the enemy, in enemy fire,” Bisek said. “And I wasn’t, I was right in enemy lines, but didn’t qualify, so I gave up on it. Then Dick Pohorsky heard about it.”

Pohorsky, a Vietnam-era veteran who has researched Purple Heart criteria, continues to reach out to Iowa’s congressional delegation.

The U.S. Army Human Resources Command lists service members “who are killed or wounded in action by friendly fire” among those who qualify for the Purple Heart.

Related: Remains of sailor killed at Pearl Harbor laid to rest in Iowa

Bisek, who remains connected to his Czech heritage, grew up in northeast Cedar Rapids in a neighborhood known as “Little Mexico” near the railroad tracks by Quaker Oats, where his mother, Libbie – a single mom – worked off and on.

“We had an outside toilet there and when we moved in that house, it didn’t have electricity,” he said of their home. “The YMCA was only about two or three blocks away and I spent a lot of time sneaking in the Y there, in the gym.” He also recalled fishing in the nearby slough.

His mother paid $7 in monthly rent, and some months, didn’t even have enough to pay that amount.

Longtime friend Lou Stepanek recalls meeting Bisek when they both played league basketball.

“He was one of the best basketball players,” said Stepanek, who now drives his friend to Czech Plus Band concerts in Czech Village and other social events.

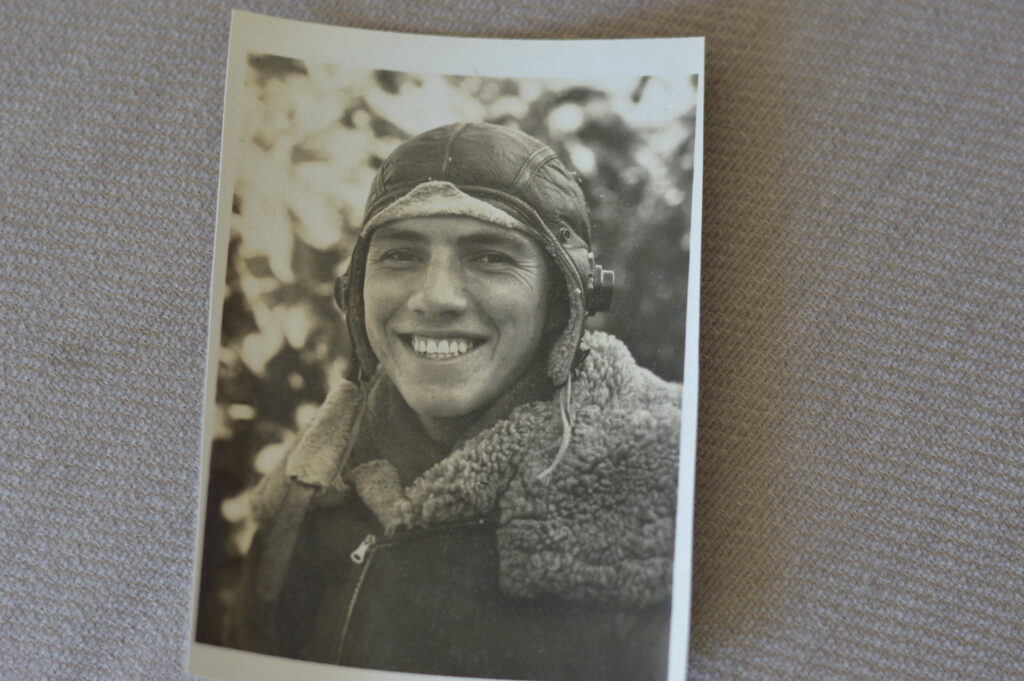

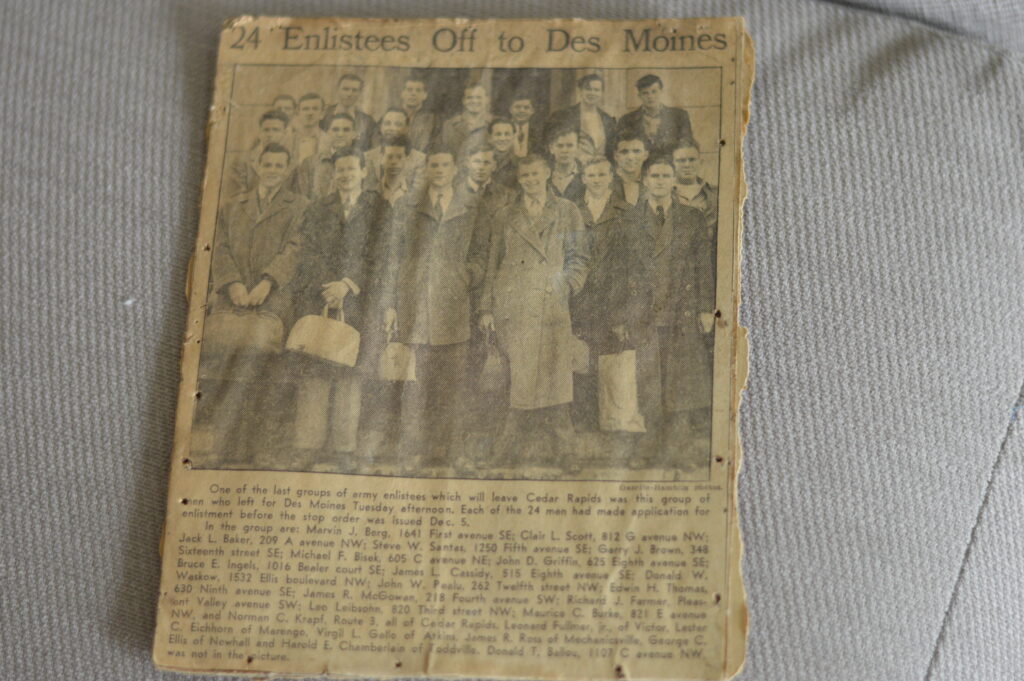

Bisek excelled at sports at McKinley School. He graduated in 1941 and enlisted in 1942, at age 19.

“I was paying off this car and running around with these girls,” he said, noting that he worked as a “blueprint boy” at Iowa Manufacturing at the time and joined the military with some of his friends, including one who enlisted after only finishing 11th grade. “I didn’t want to be drafted, but I had no doubts about going.”

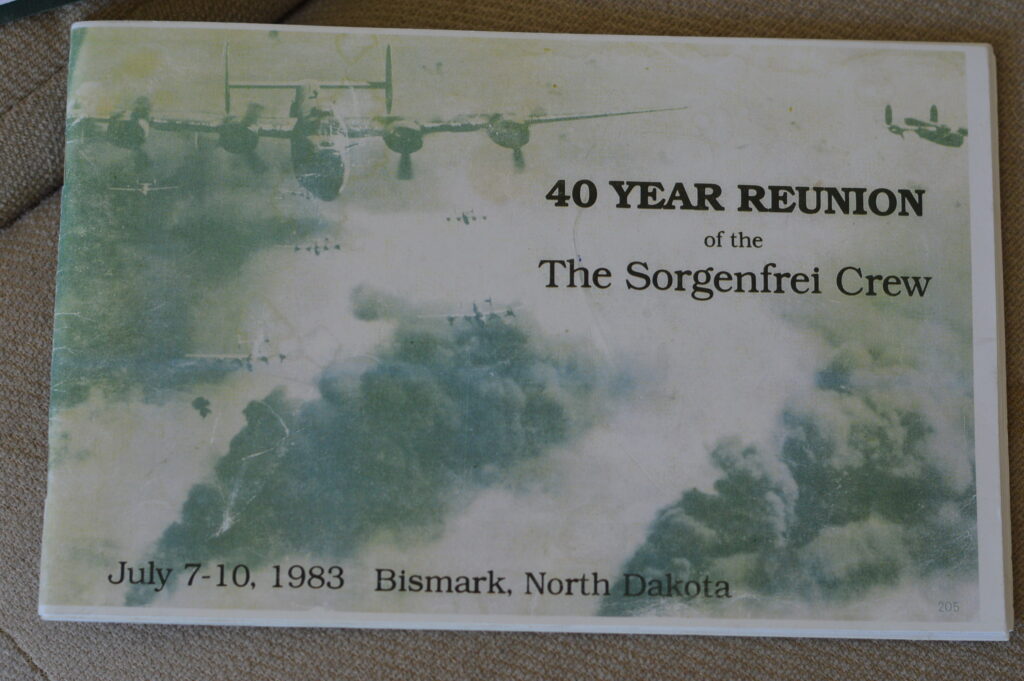

Bisek was not a regular crew member of the B-24 Liberator bomber, known as the “Sorgenfrei Crew,” for their pilot, Ken Sorgenfrei.

The 10 service members, with Bisek added as an aerial photographer and gunner, were assigned to the 460th Bombardment Group of the 762nd Bombardment Squadron. Bisek had been on 22 missions, while the Sorgenfrei Crew was on its 44th, and final, mission, on July 19, 1944.

A narrative of their story, written by Pierre Montaz, who was part of the French resistance that met the crew after they parachuted into the French Alps, described extensive shelling even before reaching their target of marshalling yards – a network of railroad tracks and switches – in Munich.

“Bullets and shells criss-cross all around, the smoke of explosions darkens the sky,” Montaz wrote in “Eleven Americans came from the sky and were saved by French Partisans.”

“A B-24 dives down, spinning like a dead leaf,” the narrative continues. “Another one, hit by a shell right into her cockpit, is turned instantly into an enormous fireball, with wings and tailplane projecting out of it.”

Of 31 bombers in the formation, seven did not return to the base that day.

Hit by German anti-aircraft artillery, the Sorgenfrei Crew’s B-24 ended up with just two of its four engines, when the pilot decided to try to land in neutral Switzerland, rather than attempting the flight back to Italy.

When one of the remaining engines misfired, Bisek remembered dumping out 50-pound containers of ammunition and other heavy items, including his hefty camera, to lighten the load.

Sorgenfrei finally ordered the crew to bail out when it appeared they might be over Switzerland. When it came Bisek’s turn to jump, his parachute opened when it caught on a handle inside the bomber.

“I gathered the canopy in my arms. I held it all pressed hard on my chest, jumped into the air and then let everything go,” the “Eleven Americans” book quoted Bisek as saying. “I knew our Lord was with me.”

He saw the plane explode and crash while he was still parachuting to the ground.

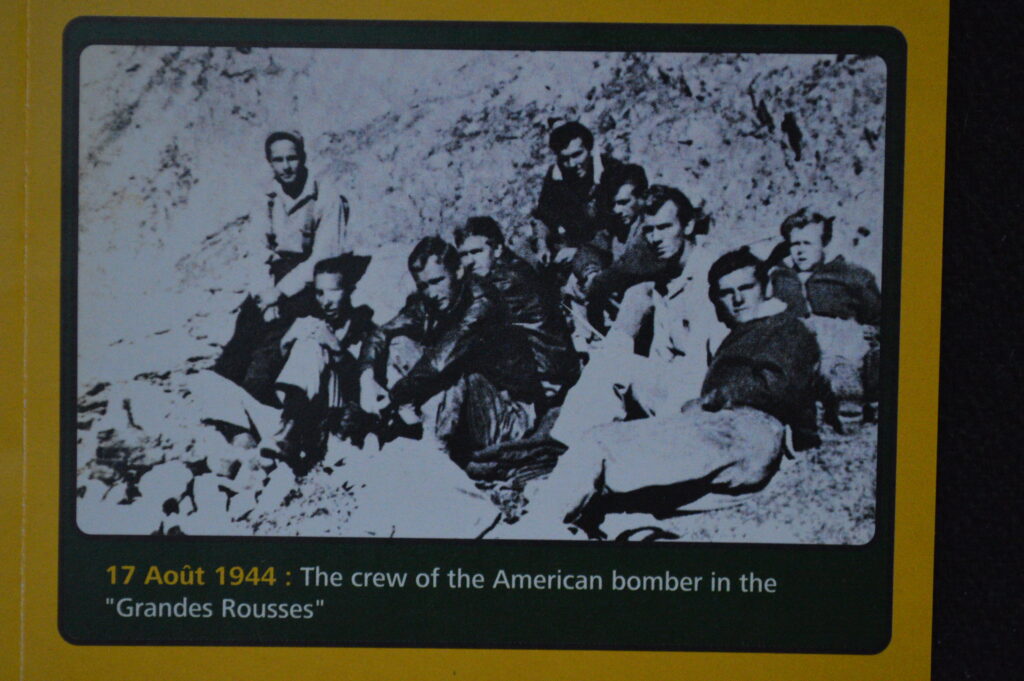

Both the French resistance and German occupiers witnessed the eleven parachutes reach the ground, but the French made it the site first and took the American crew into hiding in the Alps.

Bisek recalled being given a woolen blanket.

“I had that thing every night because it got cold,” he said. “Sometimes we’d just sleep outside and sometimes there were huts where we’d sleep inside.”

They remained in France for more than one month.

The German army had massacred Maquis of Vercors patients at the cave of Luire weeks before, heightening concern that the same would happen to another hospital where members of the resistance were recovering.

Patients of the surgical hospital, which had operated at Alpe d’Huez, were relocated to the countryside, aided by Bisek and the other Americans, who carried stretchers, ran back and forth with supplies and stayed with the wounded as they crossed the mountain.

The story of the hospital evacuation is told in historical markers placed along the route taken in the French Alps, usually only traversed by experienced mountain climbers.

Among the moving stories told in the markers, one of the patients, whose Achilles tendon had been severed, attached a nail to the tip of his shoe with a string that he pulled to move his foot forward with each step.

Photos of Bisek and the other airmen are included in a brochure of the historical route that details the evacuation, as well as in the book written by Montaz, who just recently died.

Bisek remembered seeing Germans within eyesight while the crew stayed with the patients on the mountainside during fierce battles, but all 11 Americans survived.

As American troops liberated that region of France later in August 1944, the crew’s pilot traded his flight suit for a Frenchman’s German luger pistol, which fired at a gathering, going through the pilot’s leg and then through Bisek’s leg.

“It felt like a firecracker went off,” he said. “I stood up, and here blood was coming down my leg and there was a bullet hole in my pants.”

He was taken to a field hospital, and then to a hospital in Italy.

Bisek was sent to Biloxi, Mississippi, after recovering in the hospital, where he met his future wife, Myron “Myra,” Moore, a church pianist. They married in 1945 and the couple had three children. She died in 2012 after more than 66 years of marriage.

He ended up as a draftsman at Iowa Manufacturing, working 40 years in the engineering department.

The last survivor of the Sorgenfrei Crew, Bisek’s vision and hearing aren’t what they once were, but his memory remains sharp. He is more concerned about correcting his military service records than he is about the Purple Heart, but appreciates Pohorsky’s efforts. As of this fall, they heard again that those efforts had not come to fruition.

“It would be a good legacy for the family,” Bisek said of the medal. “My blood is over there. I was fighting for the country.”

MORE: See photos as two WWII veterans were honored during a special event

[…] Related: WWII veteran awaits word on Purple Heart […]

[…] Read more of Bisek’s story. […]

[…] Read about Mike Bisek’s WWII story […]

[…] the Cedar Rapids man did not see combat, others were more dramatic, such as the story of Mike Bisek, now 101, who parachuted with the rest of his crew from their B-24 bomber over Nazi-occupied France […]